SAKES CLASSIFICATION

The world of sake does not yet have the complex legislative structure associated with the wine world, with A.O.C., D.O.C., I.G.P., etc. Today, there are only five Geographical Indications (G.I.) in Japan. However, there are "official" and "unofficial" terms to describe the history and production of the sake contained in every bottle. Unlike a spirit such as vodka or gin, whose production method or the products used in the distillation (potato, beet, cereals, etc.) rarely appear on the label, the label on a bottle of sake is full of useful information. Although the information is often in Japanese, it creates a real identification for each bottle of sake.

Officially, the legal and mandatory information on sake labels is as follows: ingredients such as rice, water and koji, alcohol content; date of production; product category; and the name and address of the brewery. But a majority of producers also use both the back and front labels to provide the consumer with even more detailed information: type of rice, percentage of rice polish, sake meter value, etc.

OFFICIAL CLASSIFICATION OF SAKE

The legislation and the classifications concerning sake have evolved continuously over the years according to the trends. The first system dates back to 1943. That year, the government established the Kyūbetsu Seido, which includes three different categories: Special Class, 1st Class and 2nd Class. This classification was based on a tasting of the sake by government officials, who then ranked it according to its quality. Regardless of the production (whether or not alcohol is added, the percentage of polishing, etc.), the higher the rank obtained, the greater the taxes paid by the kuras (breweries). The system was abandoned in 1989 when some kuras asked for a downgrade to avoid high taxes. As a consequence of this classification system, the concept based on promoting quality by highlighting high-ranking products had the opposite effect.

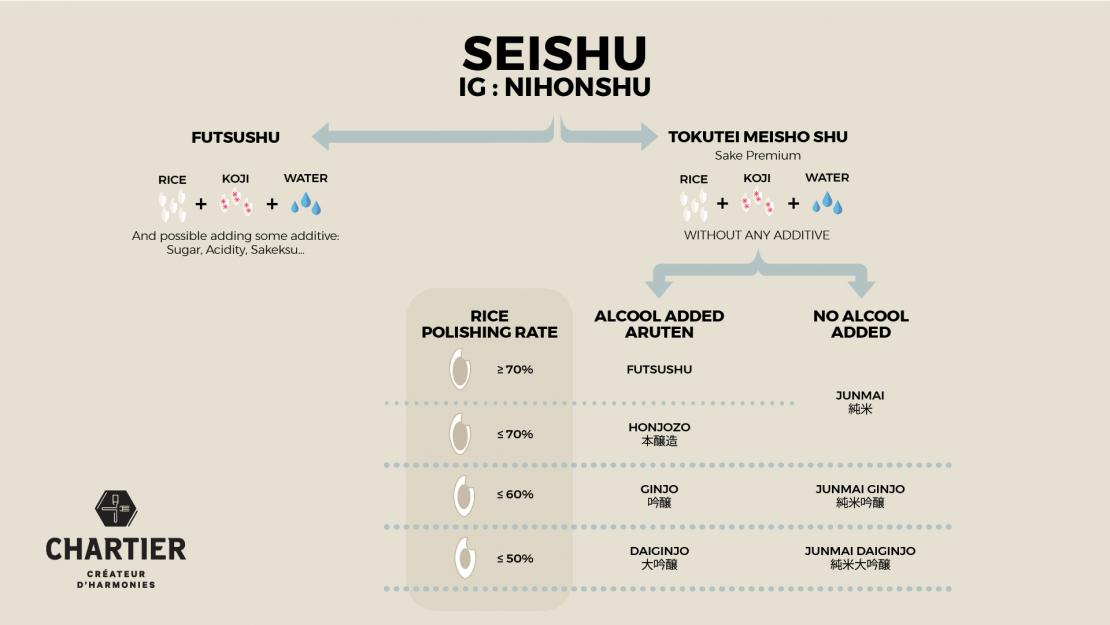

It is only since 1989 and 1992 that the official and current classification has been in place; it emphasizes three main criteria:

- addition or not of additives;

- percentage of rice polishing;

- addition or not of alcohol (aruten or junmai).

This classification was made possible by significant technical improvements, such as increased rice polishing, which also led to the advent of well-defined styles, including the return of the junmai-type sake that had disappeared after the Second World War. (For more details, see our report Aruten Vs Junmai).

This classification's primary purpose is to help the consumer quickly get an idea of the organoleptic profile of a sake through the front and back labels.

CLASSIFICATION SCHEME

The following grades are optional on the bottles. If no grade is indicated, the sake will be a futsushu. As in the world of wine, more and more kuras highlight their product and their know-how, going beyond what is legally required, simply by downgrading to NIHONSHU.

This official classification mainly limits income because it creates price ranges: for example, a junmai ginjo sake must necessarily be in a specific price range because junmai is in a different price range. The birth of this unofficial counter-current, led by the new generations and the creation of G.I.s, could eventually lead to a change in the official classification.

TOKUBETSU (特別)

"Tokubetsu" is a word often used and inscribed on sake bottles that means "SPECIAL." But what makes a sake TOKUBETSU? It is often a sake that has been polished 60 % or less and uses different rice. To be classified as “tokubetsu” the sake must be different from other sakes from the same kura (and not from the market as a whole). This type of sake is often considered by the toji (master brewer) to have a little more character or use a different production method (kind of rice, polishing, koji, shubo, etc.) In other words, everything in the making of this sake may be special (tokubetsu), as long as the kura does not produce other sakes that are similar.