THE ART OF MAKING SAKE

We will address all the steps of sake production in a series of upcoming articles, detailing the options, the effects, the history, and the evolution of sake-making. Our goal here is to review how sake is made in headline form, to get a full picture.

The most important thing to know about sake is that the rice used does not produce fermentable sugars, unlike those found naturally in fruits like grapes. Since sugar is the basis of all alcoholic fermentation, sake cannot be made without some form of transformation prior to alcoholic fermentation.

How do you produce alcohol with cereals?

Cereals produce starches, which, after enzymatic transformation, become sugars and develop alcoholic fermentation.

STARCH -> SUGAR -> ALCOHOL

Is the process the same as making beer?

· Yes: because the concept of turning starch to sugar, or enzymatic conversion, is the same. In this case, the barley is malted to obtain, among other things, the type of sugar necessary for alcoholic fermentation.

· No: because the process is different. With beer, brewers use malting or germination to create sugar. This method cannot be used when making sake because the husk is removed when the rice is polished.

So how is it done?

· Using koji! The special fungus is sprinkled on parboiled sake rice and the starches are then transformed into sugar. This step is perhaps the most important of sake-making because it is part of the future development of the sake's aromas and texture during the alcoholic fermentation that follows the koji stage.

This will help you understand the basic principles of the first step in the sake-making process! Please, note that in this Sakegraphy, we will be returning to the subject of koji on a regular basis; we believe that the term "koji" could even be translated as the "terroir" of sake, as its impact on the aromatic profiles and different textures of future sakes is so important.

THE FULL PROCESS

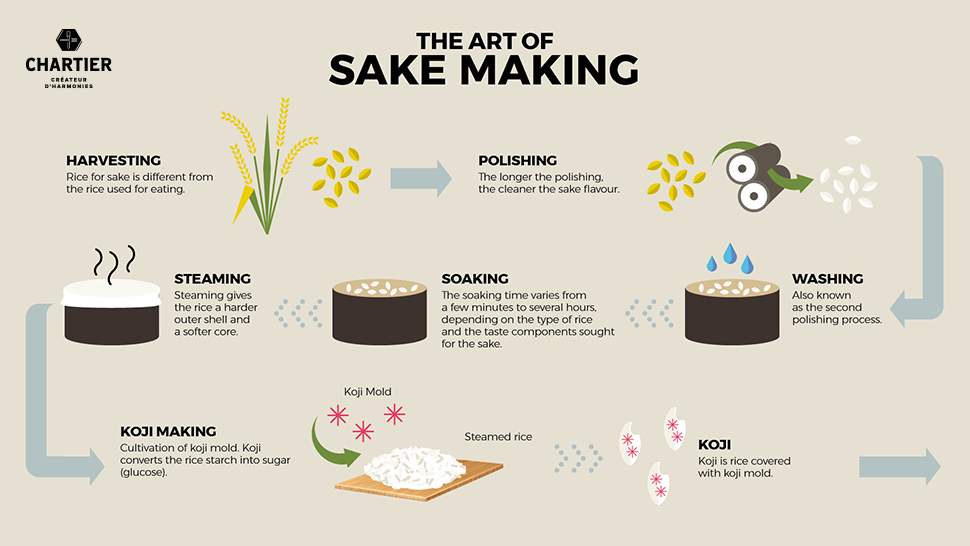

Many DIFFERENT TYPES OF RICE can be used to make sake. Sake rice has different characteristics than rice used for cooking: it is bigger and stronger, and it has more starch and fewer proteins. The first step in sake production is choosing the right rice.

Sake rice is POLISHED before use to remove impurities and to reduce the presence of certain nutrients, while keeping only the starchy heart of the grain. This is an important step, since it will define the category and characteristics of a sake:

- Futsushu polishing: ≥ 70 %

- Junmai: ≥ 60 %

- Honjozo: ≤ 70 %

- Ginjo: ≤ 60 %

- Daiginjo: ≤ 50 %

The rice polishing ratio determines how much of the rice grain remains. A 60 % ginjo indicates that 60 % of the rice remained, after having removed 40 %. We will regularly publish content about polishing and the different classifications soon; because for us, this stage, like the koji stage, is one of the most important in terms of the impact of the aromatic profiles and the different textures of future sakes.

The rice is WASHED with water to clean impurities, then SOAKED in water to ensure all the grains have the same level of humidity for uniform cooking.

COOKING the rice is important so the fungus (the koji) can reach the starchy core of the rice, and thus trigger the process of transforming the starch into fermentable sugars.

Between 20 % and 30 % of the rice used to make sake serves for KOJI. This microscopic fungus, known scientifically as Aspergillus oryzae, is sprinkled on top of rice that has been previously washed, soaked and parboiled to convert its starches into sugar.

Not all the rice is used as Koji because koji gives it a naturally strong flavour, reminiscent of nuts and chestnuts.

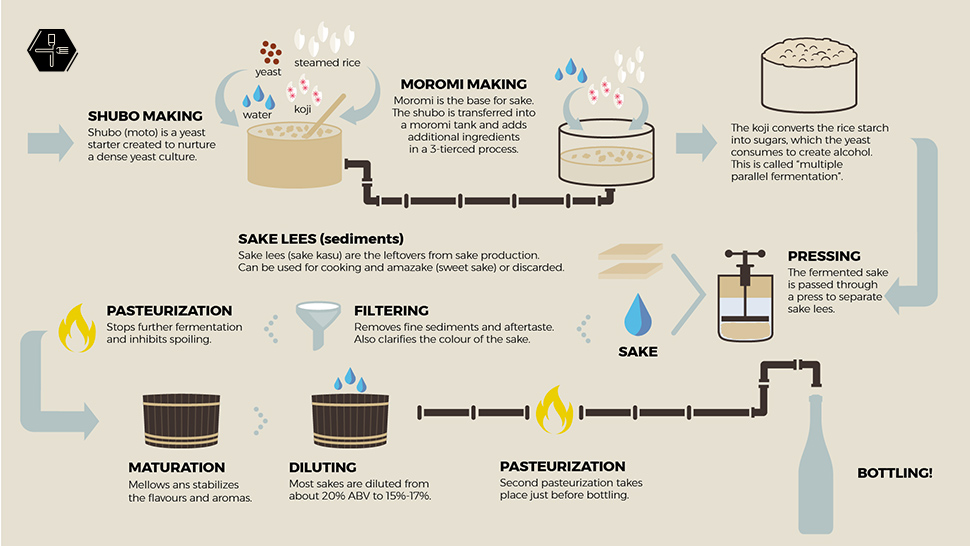

SHUBO or MOTO is in fact a small quantity of mother of sake (starter rice), made by mixing kome koji (rice processed by koji ), kake mai (parboiled rice), water and yeast.

A small batch loaded with bacteria development can convert:

- starch into sugar (by the action of the yeasts on the sugars of the rice transformed by the koji);

- sugar into alcohol (yeast).

There are different ways to make shubo (mother of sake or starter rice):

- the ancestral methods: bodai moto, kimoto, yamahai;

- the modern methods: sokujo, ko on toka moto, kobo shikomi.

Shubo can be compared to sourdough in bread making; a small proportion is used to stimulate production.

WATER plays a crucial role in sake-making. There are many qualities of water and not all of them can be used to make sake.

- Hard water: contains more nutrients, which means more food for the yeast, resulting in a faster fermentation.

- Soft water: contains less nutrients, which means less food for the yeast, resulting in a slower fermentation.

YEAST is usually bought through the government organization Brewing Society of Japan.

Each yeast has specific characteristics. The most popular are yeast # 7, # 9 and # 14.

For the Tanaka 1789 X Chartier project, we are using three types of yeast: the classics # 7 and # 6 which provide aromatic richness and length in the mouth as well as Miyagi B3, a local yeast from the Miyagi region, where the Tanaka 1789 brewery is located. This gives us the opportunity to sign the local, not to say "terroir" profile of Miyagi, which allows us to make sake with excellent length on the finish and vibrant acidity, in the manner of great Burgundy white wines.

Shubo is loaded with bacteria and ready to start working. The toji (master brewer) then proceeds with three more steps, adding more kake mai (parboiled rice), kome koji (rice transformed by koji) and water to create a bigger fermentable batch called MOROMI. The temperature is increased, yeasts wake up and fermentation begins!

Shubo can be compared to sourdough in bread making; a small proportion of which is added to boost production.

Once fermentation is complete, the Toji has some crucial decisions to make finalize his SAKE.

- ADDING ALCOHOL OR NOT ADDING ALCOOL (as is the case with JUNMAI-type sakes) (more info in Article 002).

- PRESSING to separate solids from the liquid.

- FILTRATING, NOT FILTRATING, FILTRATING A LITTLE BIT OR NOT AT ALL (as is the case with Nigori-type sakes).

- PASTEURIZING OR NOT PASTEURIZING (as is the case with Nama-type sakes).

- ADDING WATER OR NOT DILUTING (as is the case with Genshu-type sakes).

The process of making sake takes time, between one and two-and-a-half months, depending on the quality. The toji (brewmaster) plays a crucial role. His job is to transform the rice into clean, aromatic sake. And during the 6-month production season in winter, work inside the kura (brewery) goes on 24 hours a day, 7 days a week!

If you are still curious to know how each step, each element plays a role in making sake, SIGN UP FOR OUR SAKEGRAPHY to receive updates when new articles are released.

STAY CONNECTED!

WELCOME TO SAKE WORLD!